Queen of Europe was once one of Angela Merkel’s many nicknames. But now Germany’s powerful chancellor is poised to turn her back on politics following this month’s elections, I’m not sure that royal label will stick. True: Angela Merkel is, by far, the longest-serving amongst current EU leaders. She’s participated in an estimated 100 EU […]

Queen of Europe was once one of Angela Merkel’s many nicknames. But now Germany’s powerful chancellor is poised to turn her back on politics following this month’s elections, I’m not sure that royal label will stick.

True: Angela Merkel is, by far, the longest-serving amongst current EU leaders. She’s participated in an estimated 100 EU summits, not infrequently being described as “the only grown-up in the room”.

True, too: she memorably helped steer the bloc through the migration crisis, the euro crisis, Covid-19 and, to an extent, even Brexit.

But this is a tale of two Merkels.

Her European legacy, like her domestic one, is mixed. The criticism levelled at her back home – that during her 16 long years at Germany’s helm, she was a Krisenmanagerin, or crisis manager, typically waiting till the last moment to act; a pragmatist but no visionary – can also be applied to her record on the European stage.

And that matters, long after Angela Merkel leaves politics.

Merkel the pragmatist may have helped the EU scrape through numerous existential crises to survive another day.

But Merkel the non-visionary arguably leaves the bloc weaker and more rudderless than it might have been had she used her long-term position as leader of the EU’s richest and most influential nation more decisively.

Take the 2015 eurozone crisis. Even Greece’s fiery, if short-lived Finance Minister, Yanis Varoufakis, admits Angela Merkel saved the euro by keeping his country in the currency, despite its financial straits.

“It is true that, in the end, she was responsible for keeping the eurozone together because if Greece had exited I do not believe it would have been possible to keep it together,” he told me.

“But I have some very serious disagreements with the policies she followed. She never had a vision about the eurozone. She never had a vision about what to do with the eurozone once she saved it, and the manner in which she saved it became very divisive. Both within Germany and within Greece.”

Yanis Varoufakis cites the big austerity measures forced on Greece, not solely but largely at Germany’s behest.

I was in Athens reporting as anti-German and anti-EU resentment spilled on to the streets in 2015. Protesters waved placards of Angela Merkel sporting a Hitler moustache, others burned EU flags.

Spain and Italy were also forced to face what many taxpayers viewed as hardcore and unfair austerity measures, forced on them, they believed, by Angela Merkel.

Italy transformed from what had been a passionately Europhile into an ardently Eurosceptic member state.

Angry voters told me they were convinced eurozone rules had been designed in powerful Germany’s interest, to favour its lucrative export industry. They said they failed to see the point of being in a European union or common market if stronger, richer members like Germany didn’t help the weaker, struggling ones.![]()

Where were German taxpayers when you needed them, they wanted to know.

This leads to another criticism leveled at Angela Merkel: that ultimately hers was a Germany First doctrine in Europe.

Hardly surprising, you might say. Firstly, because every elected leader is likely to prioritise their nation. But then – and this is peculiar to Germany – because of its Nazi past. Germans and their chancellors are often painfully wary about taking on a prominent leadership role in international circles.

So is that Queen of Europe title deserved?

Chancellor Merkel intervened to rescue the eurozone, but she also provoked a deep north-south divide within the EU. A divide that reappeared during the migrant crisis and at the start of the Covid pandemic – with southern Europeans feeling abandoned, to face the brunt of these emergencies.

Until they no longer were. Largely thanks again to Angela Merkel, even if she tended to act very late in the day.

That is why I say her EU legacy is mixed.

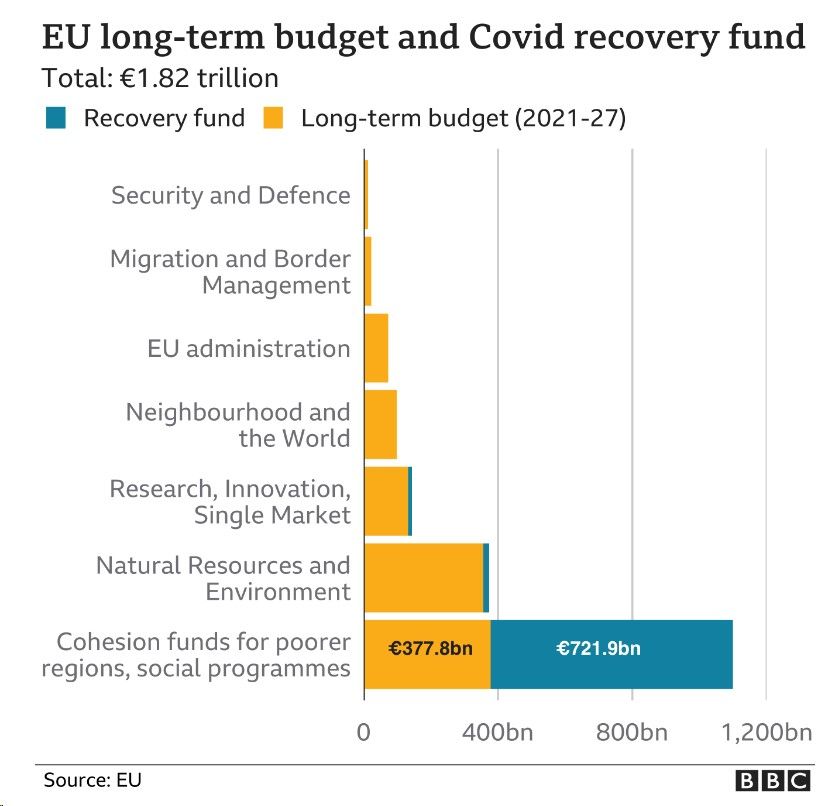

The Covid-19 crisis, unlike the euro crisis before it, persuaded her that richer countries like Germany should indeed shoulder debts of poorer EU countries, in this case those suffering disproportionate economic effects of the pandemic.

In so doing, she set a striking precedent in the EU. A radical position for a German chancellor to take, especially considering traditional pressures at home to carefully balance the books.

France’s Economy Minister, Bruno Le Maire, was a key architect of the EU’s Covid recovery fund, jointly proposed to EU leaders by Mrs Merkel and President Emmanuel Macron.

He described it to me as a game-changer for the EU thanks to Angela Merkel’s courage: “She proved to be able to take decisions against the current way of thinking in Germany and in favour of the better integration and better efficiency of the European continent.”

Mr Le Maire believes Chancellor Merkel saw the future of Europe was at stake if she didn’t sign up.

Another point of view is that once again Angela Merkel was acting first and foremost in Germany’s best interest. She possibly became all too aware the EU’s single market could collapse if Italy, Spain, France or others were suffocating economically because of the pandemic.

The market is a key money-earner for German business. So Angela Merkel the crisis manager rolled up her sleeves and took dramatic, pragmatic action. It made history and headlines in Germany and beyond.

Though not quite to the heady extent sparked by Merkel’s answer to the EU migrant crisis.

When in late summer 2015 Angela Merkel opened Germany’s borders to more than a million refugees and asylum seekers, she made front pages the world over – lauded by some, derided by others.

Back home, some proudly boasted of their country’s Willkommenkultur, their culture of welcoming others, symbolised by Angela Merkel. Others, incensed by the arrivals, flocked to the far-right AfD, spurring it to become the first extreme-right party to win seats in Germany’s federal parliament since the end of World War Two.

The impact of her migration decision on the EU was as considerable, as it was mixed.

The EU won the Nobel Peace prize in 2012. Yet, just three years later, its member states were slamming their frontiers shut on one another to keep out refugees, many of them fleeing the war in Syria.

The German leader’s actions helped resuscitate the bloc’s reputation as a key defender of human rights, set out in Article 2 of the EU’s founding principles.

US President Barack Obama was inspired, according to Ben Rhodes, who was Deputy National Security Advisor and the president’s right-hand man.

“This was an era Obama was in, when there were very, very few political leaders in the world who would ever do something that they knew was going to be politically damaging because they believed it to be the right thing.

“When Merkel decided to take in all of those refugees it was obvious there would be political blowback to that and Obama was incredibly moved by that and by the way in which she defended it.”

According to Mr Rhodes, Barack Obama encouraged Germany’s chancellor to speak out more forcefully in defence of Europe, especially after Donald Trump’s election victory and the Brexit vote in the UK.

Even though the chancellor herself was reluctant, he apparently pushed her to run for a fourth term. By late 2016, Mr Obama had come to believe that Angela Merkel and Berlin would now have to be “the centre of gravity for the liberal democratic order”, said Mr Rhodes.

Brussels basked in Angela Merkel’s glow.

On the other hand, you could ask why Angela Merkel didn’t pressure EU leaders to better prepare ahead of the 2015 migrant crisis. Following events in Syria and Libya, it hardly came as a surprise. She could have used her power and influence to push for orderly legal migration channels, say critics.

Instead, desperate refugees and asylum seekers lost their lives at sea trying to cross illegally to Europe, and EU countries put on an unedifying spectacle in trying to keep them out.

The chancellor later came under fire from Amnesty International and refugee groups for her key role in then brokering a controversial deal on behalf of the EU with Turkey’s autocratic president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The agreement tasked Turkey not only with preventing refugees and others from boarding smugglers boats bound for Europe, but also with starting taking back those who managed to land on Greek shores.

And there are many more examples of “Yes, buts” when it comes to Angela Merkel, a purported EU bulwark in the defense of human rights.

Yes, this summer, she and 16 other EU leaders signed a joint letter in defense of the LGBTQ+ community, amid a raging controversy over a new law in member state Hungary. But Angela Merkel was for years also viewed by many as an enabler of Hungarian democratic backsliding.

Hungary’s self-styled “illiberal” Prime Minister Viktor Orban was until recently a member of Chancellor Merkel’s center-right EPP group in Brussels, guaranteeing it more seats and influence in the European Parliament. Alienating him was problematic, and she repeatedly stopped short of taking decisive action.

The lesson learned by Hungary and its EU ally Poland – both key partners for German businesses – was that Angela Merkel and the EU as a whole were partly unwilling, and partly unable, to take swift decisive action when it came to their human rights record and the rule of law.

Ana Palacio, a former Spanish foreign minister and ex-vice president of the World Bank Group, recently accused Germany of effectively leading what she described as Europe’s “non-strategy” to rein in its illiberal members. If Germany wanted to act to uphold the EU’s founding principle protecting human rights and rule of law it would happen, she said.

Ms Palacio also attacked EU foreign policy, laying no small share of the blame for lack of direction and “dubious decisions” at Angela Merkel’s door: from the EU’s dealings with Turkey to its Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China. That deal was signed in December at the end of Germany’s six-month presidency of the EU, to the horror of the then-incoming Biden Administration in Washington.

China was Germany’s most important trading partner for goods in 2020.

Angela Merkel is often attacked for seeming to allow Germany’s trade interests to dictate her country’s foreign policy, with a resulting influence on the EU.

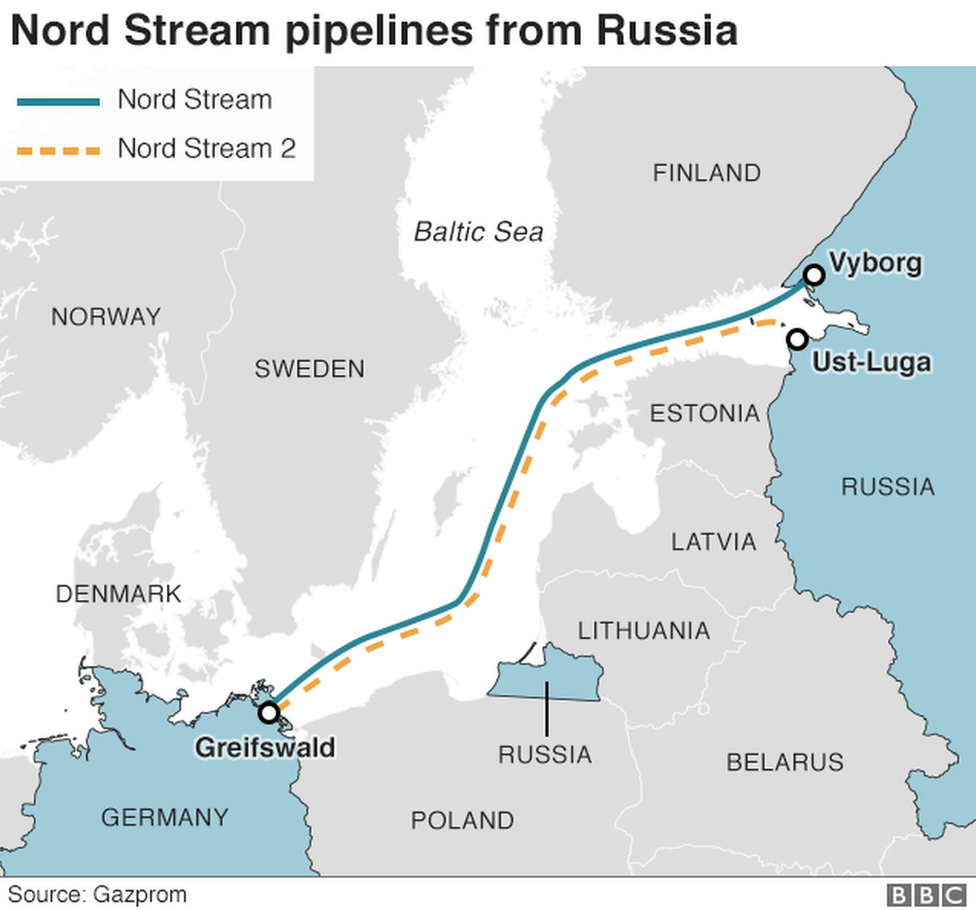

Take relations with Russia. By building the Nord Stream 2 pipeline between Russia and Germany to secure cheaper energy, she stands accused of weakening both EU political unity and strategic coherence vis-à-vis Moscow, as well as giving Vladimir Putin more leverage over an EU he has a strong interest in weakening.

Many countries in Central and Eastern Europe oppose the pipeline. Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Zelensky, recently called Nord Stream 2 a “dangerous geopolitical weapon”.

For her part, Angela Merkel insists the EU will impose further sanctions on Moscow if it abuses the pipeline.

She has been a passionate advocate of sanctions against Russia over Ukraine. And when prominent Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny was poisoned in August 2020, the German leader had him flown to a Berlin hospital, where she took the highly unusual step of paying him a surprise visit.

A mixed legacy once again.

The aim of this article is not, of course, to lay all EU ills at Angela Merkel’s door.

But when it comes to EU legacies, it’s worth taking a look, as German journalists have been doing, at her late political mentor, former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

In Brussels, he is viewed as a founding father of the modern-day European Union. He supported the idea of the euro, against majority public opinion in Germany at the time. His reasons were political, rather than economic. Helmut Kohl believed a common currency would prevent further wars between European neighbors.

Kohl also pushed for German reunification, to the cost of taxpayers in western Germany. In so doing, he brought Eastern and Central Europe that much closer to the EU, even if membership was still a far-off prospect.

Angela Merkel’s European crown doesn’t sit so well by comparison. A key EU figure in crisis-ridden times? The glue that just about kept the gang together?

Yes.

Architect of a confident, new EU future? Possibly not.

It was, and still is, France’s Emmanuel Macron who lusts after that title.

Four years ago in Paris, he requested that Beethoven’s 9th – the EU anthem – be played when he announced his presidential election victory. Nicknamed Mr Europe, he had an ambitious EU reform plan, including strategic autonomy from – or at least, less reliance on – the United States, but he needed Angela Merkel’s help.

Help to breathe back life into the so-called Franco-German motor of Europe – and help to invest German taxpayer’s money in making his 21st-Century EU vision a reality. Not the most popular idea back in Germany, as Angela Merkel was all too aware.

Her repeated push-backs and endless stalling tactics over the years, until the Covid recovery fund, led to her being quietly referred to as the Chancellor of Nein.

Berlin, I’m told, has its own nickname, Scattergun, for the French president’s administration. Apparently because of all the different ideas they keep coming up with for Europe: from having its own defense force, to environmental proposals, to a new EU trade ethos and euro currency consolidation.

Whoever Germany’s next chancellor turns out to be after this month’s election, and the race is wide open, he or she will lack the experience and gravitas Angela Merkel amassed in Brussels over the years.

Emmanuel Macron sees the Merkel-shaped hole at the head of the EU table and is hoping to fill it.

If he does, the bloc could see some big changes. The man dubbed in France the Emperor of the Élysée Palace would love to be crowned king of Europe.

First, though, he must win the French presidential election in April. And that’s no small feat.